Picture a Scientist

Season 48 Episode 3 | 1h 33m 6sVideo has Audio Description

Researchers expose longstanding discrimination against women in science.

Women make up less than a quarter of STEM professionals in the United States, and numbers are even lower for women of color. But a growing group of researchers is exposing longstanding discrimination and making science more inclusive.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Major funding for "Picture a Scientist" is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Additional funding is provided by: Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program with support...

Picture a Scientist

Season 48 Episode 3 | 1h 33m 6sVideo has Audio Description

Women make up less than a quarter of STEM professionals in the United States, and numbers are even lower for women of color. But a growing group of researchers is exposing longstanding discrimination and making science more inclusive.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch NOVA

NOVA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

NOVA Labs

NOVA Labs is a free digital platform that engages teens and lifelong learners in games and interactives that foster authentic scientific exploration. Participants take part in real-world investigations by visualizing, analyzing, and playing with the same data that scientists use.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ JANE WILLENBRING: The word that people often use is that I was "triggered."

I had a three-year-old daughter, and she came to the lab with me one weekend.

I had told her that I was a scientist before, and I don't think it had really clicked in her mind that I was actually a scientist.

(laughs) And so she came to the lab with me, and I had my booties, and I was wearing a Tyvek suit, gloves, and goggles-- the whole getup.

And she looked at me, and she was just, like, "You really are a scientist, Mommy."

And then she said, "I want to be a scientist just like you."

And that was the horrible, like... (laughs) ...sort of lose-it triggering moment that I have ever had.

And, um...

I actually... (clears throat) ...started crying at the time.

And I, you know, she's three, so she doesn't understand why I'm crying.

And so I told her that they were happy tears.

But they weren't just happy tears.

I was thinking about someone treating her like trash in 20 years, like I had been treated like trash.

The one thing that I could do to help her the most is to try and make the whole enterprise something that is welcoming to women, and that was something that I hadn't done.

♪ WOMAN: We all have images in our head.

We have images of what a woman is like, what a man is like.

When you ask somebody, "Draw a picture of a scientist," it used to be all men.

♪ WOMAN: We were just trying to be scientists.

We certainly didn't want to be seen as troublemakers or activists.

♪ WOMAN: The big picture is that women are extraordinarily underrepresented in science.

WOMAN: The message that's given is that you somehow don't belong here.

WOMAN: There's a playbook, and it was written by men.

And the men pick up on it.

They know what the plays are, and I always felt I didn't have the playbook.

(chuckles): You know, I'm just sort of feeling my way through this, this game.

♪ (car horns, distant traffic) NANCY HOPKINS: There's your standard striped version.

Beautiful, beautiful little fish.

And if you see, the males are very slender, and the females have the large belly.

Generally a good sign they're going to lay eggs.

♪ I'm Nancy Hopkins, and I was professor of biology at M.I.T.

for 40 years, and I retired three years ago.

(chuckles): Ah-hah, this is a picture of Greta.

So this was, this was the first experiment we did, really, in zebra fish.

We were still just learning the system.

At the time, I was taking care of the fish, so I was in the fish room, like...

I was literally in the lab 365 days of the year.

This is actually looking down on a fish embryo.

And about this time, there's about a thousand cells.

I think about a thousand.

And four of those thousand cells are going to go and become the sperm or the eggs of that fish, and those are the four cells.

(chuckles) And then they begin to divide.

When I was about ten, my mother got cancer.

In that generation, the word "cancer" was so terrifying, you didn't say the word.

And so she was terrified, and that certainly made a big impression on me, and I'm sure that's partly why I was interested in cancer research later on.

I went to a small, private girls' school in Manhattan.

They didn't teach a lot of math and science to girls in my generation, because people thought girls didn't like or need much math or science, but I took everything they offered and loved all of it.

♪ I went to Radcliffe.

I was 16, I guess, when I started.

In the spring of junior year, I signed up for this course called Bio 2.

Jim Watson came in, and one hour later, I was a different person.

He and Francis Crick had won a Nobel Prize for discovering the structure of DNA.

♪ This genetics, this molecular biology, it was the answer to all of the questions I'd ever had about everything; this is what life is, this is how it works.

It's going to explain everything that living things do and can do.

I couldn't imagine going on without being near this science.

I just had to be near this.

I started working in Jim Watson's lab as an undergraduate.

It was absolutely thrilling, and I thought, "Well, I'm happy."

♪ However, there was this odd, funny thing that happened.

Francis Crick was coming to visit the lab, and he was going to give a talk.

And this was enormously exciting, because, of course, Jim just thought Francis was a genius.

I thought Jim was a genius.

Jim thought Francis was a genius-- wow, how smart could this guy be?

So I was very excited Francis was coming, and I was sitting at my desk in this little lab, which was adjacent to Jim's office.

And the door flies open.

I was in the room alone, and there's standing Francis Crick.

He comes flying across the room, puts his hands on my chest and breasts, and says, "What are you working on?"

You know, looks at my notebook and says, "What are you working on?"

And I was so startled, I didn't quite know what to say or do.

So I sort of straightened up and said, "Oh, well, here, "let me show you this, I'm doing this experiment.

Somehow, this, I'm trying to do this."

And at the time, the word "sexual harassment" didn't exist-- it wouldn't have crossed my mind.

So I just didn't want to make a fuss.

I didn't want Francis to be embarrassed.

I didn't want Jim to be embarrassed.

I just tried to pretend nothing had happened.

(seagulls squawking) (keys jingle) Not losing the keys to the car is the most important part of field work.

(laughs) And hiking.

This is an area of coastline in California that is really being impacted by cliff retreat.

We're really interested in figuring out how fast sea level rise is going to impact the coastal zones.

♪ I'm Jane Willenbring.

I'm an associate professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, which is part of U.C.

San Diego.

♪ One of the things that I think is great about being someone who studies how landscapes change over time is that it is so incredibly important for maintaining our way of life, basically.

♪ One of the ways that we're trying to create resilience and adaptability to climate change impact is through figuring out what will happen to coastal areas.

One of the things that drew me to Earth science when I was starting my degree was, you get to use all of the different kinds of science to really understand how we are impacting the Earth, and people were arguing at the time about whether there was going to be this massive deglaciation of East Antarctica if we warmed the Earth just a couple of degrees.

Field work in Antarctica seemed like a perfect, you know, trajectory for my science life.

I decided to go to Boston University to get a master's degree.

I started the program in 1999.

I was going to work with Dave Marchant, looking at the glacial history of a part of East Antarctica.

He was a really important person in the field.

He even had a glacier named after him.

And I was incredibly thrilled to get the opportunity to go.

It was like a dream come true, actually.

So we were going to head out in the field in early December.

It actually takes a long time to even get there.

We went from Boston to New Zealand, New Zealand to McMurdo, and then finally, we go out with all of our tents via helicopter into the field, and then we were just there.

It's such an incredibly blue sky-- the bluest sky, maybe, that I've ever seen in my life.

You just have rock and mountains and ice as far as you can see.

It is like nowhere else.

There were four people in the group.

So there was Dave Marchant, his brother, and then also a master's student from the University of Maine, Adam Lewis.

The order of things, in, in some cases, is quite jumbled in my mind.

I do know that there was a definite break between when we were in, even McMurdo, when we were surrounded by other scientists and program officers from the National Science Foundation.

And it wasn't until we got to the field that sort of the filters were off.

There was some "Saturday Night Live" skit.

Jane, you ignorant slut.

(laughter) WILLENBRING: Dave would start off from that sort of pop-culture reference to just calling me a slut, and then "slut" went to "whore," and then "whore" went to (bleep).

♪ We'd have to deal with all of these stories about how slutty I was, and how I'd be good for this person, who is a helicopter pilot, or this person, who is his brother.

And I just wanted to talk about science.

♪ At one point, he decided to just, every time that I had to go to the bathroom, just throw rocks at me.

Little tiny pebbles most of the time.

So there are no trees to hide behind, no bushes or anything like that.

It was so embarrassing and demeaning, and so I stopped...

I stopped drinking water during the day so that I wouldn't have to go to the bathroom as much, and I ended up getting a bladder infection.

And eventually, there was blood in my urine, and I've actually had, had sort of bladder problems ever since that time.

(wind howling) We were looking for ash inside of these belts of sediment and, and boulders that form on the margins of glaciers.

These ashes can be dated, and so they're great to find.

So he had a little bit of ash on this little metal scoop.

He motioned to lean in.

And so I looked, got down really close to be able to see the individual crystals in the ash.

And at that point, he just breathed onto the spoon really quickly, and the glass shards went into my eyes.

While I was doubled over in pain, Dave looked at everybody and sort of shrugged and said, "Oops, that went a little too far."

I remember I was trying to get up a really steep slope.

It was covered with moveable debris.

So every time I would try to take a couple of steps up, I would just naturally slide down one step worth.

So it was incredibly frustrating to go up and down this thing.

Dave was at the top at one point, and I had just gotten about three-quarters of the way up the hill, and he grabbed the back of my backpack and just pushed me down the hill.

I remember just sort of weeping at the bottom of this hill.

And I just decided at that moment to just sort of let everything kind of wash over me and that I was just going to decide to do something later.

♪ I didn't know how long that later would be, because my future was still in his hands.

After we got back and then the year after.

And so it just became sort of this, like, later, like, this point on the horizon.

♪ (indistinct chatter) MAN: I'd like to welcome all of you to this convocation on a most important topic.

Together, we can do better, certainly, addressing sexual harassment.

PAULA JOHNSON: The best estimates are, about 50% of women faculty and staff experience sexual harassment, and those numbers have not really shifted over time.

If you think about science, right now, we have a system that is built on dependence, really singular dependence, of trainees, whether they are medical students, whether they are undergraduates, or if they're graduate students, on faculty for their funding, for their futures.

And that really sets up a dynamic that is highly problematic.

It really creates an environment in which harassment can occur.

Generally speaking, sexual forms of sexual harassment-- like come-ons, unwanted sexual advances-- those are actually the rarest forms of sexual harassment.

They actually don't happen very much.

Mostly you see put-downs.

JOHNSON: We use the metaphor of an iceberg to really get across the various forms of sexual harassment.

What's gotten most of the attention is unwanted sexual attention, coercion.

Those are in the public eye, and I think everyone would agree we absolutely need to address those.

CLANCY: And then you have all the stuff that's underneath.

Those are actually more than 90% of the sexual harassment.

You know, the subtle exclusions, being left off an email, not being invited to a collaboration where you're the clear expert.

Just these little moments that make a woman feel like she doesn't belong, that's a really common experience.

JOHNSON: We found that consistent gender harassment actually has the same impact as a single episode of unwanted sexual attention or coercion.

So it is not something to be ignored.

(birds chirping) RAYCHELLE BURKS: This is our shared lab facility.

So all of the chemistry professors have lab space, some corner of it, here.

♪ I'm Raychelle Burks.

I am an assistant professor of chemistry.

So we make sensor arrays.

When they're exposed to different environments, they have chemical reactions that they'll undergo.

So it might be something like phenolphthalein, which, anyone who's watched, like, the crime shows, and it's, like, "We found this," you know...

They swab something, and then it's, like, drop, drop, another bottle, drop, and they're, like, "It's blood."

And it's gone from being colorless to being bright pink.

The things I'm trying to find are usually the nefarious things.

So biological and chemical weapons, explosives.

I design systems to find those.

The types of tests I'm building are for natural disaster/ war zone situations, where you're trying to do a quick screen.

And it could be Hurricane Maria or Hurricane Harvey.

Especially Flint.

NEWS ANCHOR: Flint residents filed a federal lawsuit accusing the city and state of endangering their health by exposing them to dangerous lead levels in their town water... NEWS ANCHOR: Flood waters in New Orleans are full of sewage and bacteria that can make people sick.

Federal officials joined local agencies in urging... You know, from a social justice angle, people still need some kind of testing metric and to get an answer, especially in that kind of environment.

You know, is there some type of test where you're not pricing the user out of it?

That's what my group does.

By using all of this information and statistics, get to the point where the final product, we hand it off to the user, and what they get is a simple-to-use test.

Like, kind of on the pregnancy test, where it's, like, "Okay, so double lines means... What again?

Single line means..." You know, like... (laughs) But you have, like, that little diagram.

I grew up in the L.A. area.

Very big high school, 3,000.

And the classes are packed.

I don't remember any teacher in high school being, like, "You can do it," in the sciences in any way, but I just kept showing up.

It's funny, a lot of the scientists I think of growing up are actually fictional characters.

"STAR TREK" NARRATOR: To boldly go where no man has gone before.

Like, Uhura was a scientist.

Progress report.

I'm connecting the bypass circuit now, sir.

BURKS: And she was in charge of comms, but really, she was a scientist.

Going through college, you know, there were no Black women chemistry professors that I had.

I heard that they existed, though.

(laughs): But I never had any.

I went to get a PhD in chemistry so I would have more employment options.

♪ There are lots of things I love about the sciences and I love about academia and my job.

But then there's also some real bull(bleep).

♪ In academia, as women of color, we're going to have different types of abuse from different people.

I remember when I was in my office once, sitting at my desk, at my computer.

Like, I've got, you know, papers spread out.

And someone comes into my office, and for some reason, assumes I'm the janitor.

I mean, I've been in meetings where you've made a suggestion or said, "Well, what about this?"

And it was like you'd never spoke at all.

But if a white guy says it, you're, like... And now it'll magically be heard, everybody watch this.

Sometimes you get these critical emails, and criticism is something that, as a scientist, you have to get used to.

But I think it's, is it appropriate?

There's been some cases where I'm, like, "Wow, this is wildly inappropriate."

You don't get to just say what you'd really want to say.

Like, "How dare you?"

I'm going to be seen as, like, the angry Black woman trope anyway, but you have to, like, "Okay, how do I minimize that?"

So you spend all this time trying to craft a response or an approach of how to, like, deal with it.

It may not seem like a long time-- five minutes, ten minutes, 15 minutes, 20 minutes.

And I think about all of that time added up.

That's time I'm not spending on grants, on writing papers, on networking with my peers, on just doing research with my students, because I'm trying to navigate these oppressive systems that people who are not in the marginalized communities, not only do they not have to do that, they don't even...

It doesn't even register.

It's not something that they even think about, let alone it being a time suck in their schedule.

♪ You have to remember that, because I'm, like... (whispers): "How's this person, like, able to do, like, all this stuff?"

And then you're, like, "Oh."

(laughs) "That's because they're not having to do any of that stuff."

You know, and that's, that's the other thing you have to kind of remember.

♪ HOPKINS: When you're starting out in science, it's kind of like getting an airplane up off the ground, you know, you've got to get... You've got to get going.

Make enough discoveries that you can become known.

So I just kept working.

A couple of years passed, and suddenly I was called by M.I.T.

and asked to apply for a faculty job.

But I did begin to have trouble as a junior faculty.

These post-docs, I think, saw you more as a technician than a faculty member.

The reagents you made and so forth, they saw it as just a...

They could just go and take anything they wanted, because after all, what were you?

You were just a technician, I guess.

♪ I'd have to wait to use my own equipment, and they would take things out of the incubator.

Just take them, you know, and I didn't want to tell them not to, because in that era, women had to be nice to everybody, they had to be polite to everybody.

You couldn't, you know, be unpleasant, or people would say, "Oh, there's that nasty, difficult woman."

And then everybody would avoid you.

So I was, didn't want to do that.

And the other thing I found is, I started publishing papers, and then I found you'd publish the papers, and you would have trouble getting credit for the discovery.

Everybody feels that way in science.

Everyone thinks their work is undervalued, and they're under... Everyone feels that way.

But I thought, "No, this is somehow different."

And, again, I didn't tell anybody that, because they, who's going to believe you, you know?

Nobody.

So I just kept working, and I got promoted to associate professor, and I guess the letters were very, very good that came in.

So I got tenure.

♪ I began to have these significant problems.

It was probably about 1990, roughly.

I was going to set up zebra fish.

You can do genetics in fish, genetics of behavior, and I needed to get 200 square feet of space to put the fish tanks in, and I couldn't.

One man said to me, "You don't think you could really handle a bigger lab, do you?"

And I went to the people administering the space, said I'm senior faculty, and I had less space than some junior faculty.

The man said, you know, "That's not true."

So I literally thought, "Okay, I have to show him it's true."

Took a tape measure, and I would go around the building when there weren't people there, and go into the lab, and I would measure the lab, write down the space.

And I would color in the spaces that each person had, so I could tell how much space.

And I'd keep a chart, and I'd add it up, so it took a lot of time.

My idea was that then I would demonstrate, "Here's the data.

I have less space, so how can you argue with this?"

But when I got the measurements and showed them to the person who was in charge of space, he refused to look at them.

And that's when I became a radical... activist, I guess, against my wishes.

♪ WILLENBRING: You know, I expected science to be working really hard for something, and I was completely sort of set up for that being the case.

In fact, I enjoyed the struggle and hardship of doing field work, especially when I was younger and my bones didn't creak so much.

(laughs): And...

So I was accustomed to that kind of struggle, and adding to that with a kind of struggle that's completely unnecessary and gratuitous was hard to handle, and did make me think about quitting a couple of times.

I had...

I had other jobs picked out.

I would see a bus pass and think, "Bus driver, that sounds pretty good."

♪ The things that really got me the most were him telling me that I'm (bleep) stupid and that I'll never have a career in science.

Those things that sort of got under my skin in terms of my competence and my abilities as a scientist, I never really stopped thinking about those.

I didn't really tell many people at all.

It was really something that I didn't talk about.

So I just kept doing my work.

I finished my PhD, then I did a post-doc, and then took a faculty position.

And the whole time, I'm thinking a little bit in the back of my mind that, you know, "Remember, you sort of told yourself that you were going to do something about this?"

And I just never did.

Look at that structure on the beach.

Oh, yeah, they're doing some construction on that building.

Mm-hmm, yeah.

It's been a while since we've been on the beach, huh?

It's been raining so much.

(chuckles) Oh, we should remember where our shoes are.

Remember, we made that mistake before.

(laughs) ♪ WILLENBRING: I knew he was still a faculty member there, and I'd heard through the grapevine that he was still harassing women.

After that day with my daughter in the lab, at that point, I realized that, you know, I had tried to create an environment that was very science-friendly for her, and done all of the things that women do to try to get other women or their children into science.

The one thing, though, that I could really do was something that I hadn't done.

♪ I went and wrote the Title IX complaint, the first draft of it, that night.

♪ And it was, it was a bit liberating, I have to say.

It was 17 years after the fact.

I definitely waited until after getting tenure.

I told Adam Lewis, the person who was in the field with me.

I'd always imagined saying something about how badly I was treated during that field season, and I was expecting him sort of to say, "I don't want any part of this."

And instead, he said that he's always felt guilty about that field season, and that he'd be happy to write a letter.

♪ (indistinct chatter) BURKS: This conference, like a lot of science spaces, there's always a bit of discomfort.

It's not designed for my comfort.

And it's not designed for a lot of people's comfort.

It can be, you know, very majority-heavy.

And you'll have things, like, people will call out, like, "That's a manel!"

You know, like, all men on your panel.

"That panel is whiter than the cast of 'Friends.'"

As a field, we have not made the place very accessible and inclusive.

(passing traffic) I remember I was parking in the faculty lot, where you need a faculty sticker, which was on the front of my car, and I pulled into a faculty spot because I am faculty with a faculty sticker.

(laughs) And this other person who was clear-- I mean, I'm assuming maybe she was on staff.

She leans out the window and yells at me, "Do you work here?

Are you faculty?

'Cause this is a faculty lot."

And I said, "Yes, I have a faculty sticker, and I'm going to park here."

And she looked so-- she was, like... "Well, I've never seen you before."

And I, like, went, "And I've never seen you."

(laughing): And I just pulled in and then went.

I think the higher you go up the ivory tower, the whiter it gets, and the more male, and the more hetero, the kind of majority-dominant viewpoints come out.

I mean, the fact that you can still report on how many, you know, women presidents there are of institutions, how many chairs, how many deans, you know, the numbers are so low that you're reporting on them.

You know, academia is especially historically marginalizing-- you can be very isolated.

You get used to being underestimated.

You get used to being treated a bit shabbily.

People can insult us to our face with inappropriate language and derogatory terminology, but we're the ones that are supposed to be respectful and civil.

And it's not that you take it personally.

(voice breaks): You just don't expect any different.

(tearfully): You know, for a long time, you try to fit, or put the face forward that you are this, whatever they've built science to be.

That you talk a certain way, and you look a certain way, and you try to fit into that.

And even when you do all that, you're still not considered one of them.

♪ But you just get used to that.

You get used to being invisible in the sciences.

It's weird, 'cause you're invisible in that way, but then you're hyper-visible, 'cause people are, like, "But why are you here?"

(sniffles) ♪ (elevator chimes) Wow, oh, wow, okay, so...

This was my office.

This... And that was my lab when I was a junior faculty member.

I spent so much of my life there.

(chuckles) Yeah, so I was doing these measurements, and I tended to do them at night, because I really thought, you know, people would think it very odd.

"What are you doing?

", and I didn't really want to explain to anybody, so I would go at night and odd times, and dinner times, when people weren't around, with my little tape measure here, and I would measure all the spaces.

And I do remember one night, I was in this room, which I guess no longer exists in the format it used to.

And I was, had my measure out.

I was doing the measuring.

And somebody unexpectedly-- it was very quiet-- but somebody unexpectedly walked into the room and saw me, and I remember freezing and thinking, "Uh-oh.

"Uh-oh, my cover is blown.

"Now they're going to wonder what am I doing here," so it was an odd thing.

I was a full professor.

So what was this woman doing creeping around in the night with a tape measure, measuring the lab space?

I expected to fight alone.

I didn't expect anybody else to fight with me, but I really knew that I was right.

I decided I was going to give M.I.T.

a last chance.

I didn't go back to the provost, because I was embarrassed.

You know, at first, I had this problem, now I've got another problem.

So I wrote to the president of M.I.T., and I said, "There's a kind of systemic and invisible discrimination against women."

And I wrote this letter, and I showed it to another woman faculty member, so she can see whether it would be understandable to the president.

And if she approves of that, I'm sending it.

And the woman that I chose was, of course, this woman I had revered for so long, and that was Mary-Lou Pardue.

PARDUE: From time to time, Nancy and I would get together and talk about things, and so she had wanted me to, to see what I thought about the letter.

HOPKINS: I asked her to have lunch.

We went to Rebecca's Cafe, which was just down the street.

We sat in this little corner table, noisy lunchtime crowd, and I had my letter.

She looks very serious.

And we've never talked about gender issues, and I think she's going to think I'm just some loser, you know, who really isn't good enough.

Maybe she thinks I'm not good enough, and that's why these things are happening to me.

I had no idea, so it was very embarrassing and humiliating to ask her to do this.

She reads the letter slowly, and I'm watching, and I'm so anxious, because I think she's thinking badly of me.

She gets to the bottom, and she says, "I'd like to sign this letter, "and I think we should go and see President Vest, because I've thought these things for a long time."

PARDUE: I had seen enough of the kind of things that go on that I really wanted to support her.

HOPKINS: We suddenly realized, "Gee, if you get it and I get it, there might be other people who also have figured this out."

PARDUE: So then she and I, we went around and talked to each of the tenured women in the School of Science.

SYLVIA CEYER: I didn't know her.

She came to my office in the spring of '94, and wanted to chat about what it was to be a female in the chemistry department.

It became evident that there were very, very few women in the faculty at M.I.T.

HOPKINS: 15 women in the six departments of science and 197 men.

They were such high-profile women.

Half of them were in the National Academy of Science.

Most of us didn't really-- we knew of each other, but we didn't really know each other.

CEYER: And we made sure this meeting was in a remote location, so nobody could see us.

(laughs) I have this feeling it was a very small room, and half of us were sitting on the floor.

I wanted to know if this was something that was just a biology department problem, or whether this was a bigger problem.

CHISHOLM: At the beginning, nobody really wanted to jump right in and go there, because you don't want to be perceived as, you know, weaker than, but it all just came out in little trickles, and, suddenly, you know, everybody was just letting it all hang out.

CEYER: There were comments from my male colleagues like, "Well, she really isn't as smart as she's given credit for."

No woman had ever taken family leave and gotten tenure.

Women were afraid to take it because of the stigma attached to it.

A guy said that we are a bunch of hysterical women.

(laughs): Yeah.

At that time, the problem was, women were not listened to, and this was going to be the place where every woman's opinion counted.

♪ CHISHOLM: I just remember us all marching as a, as a pack to the dean's office together.

HOPKINS: And we felt intimidated, as if somehow, you know, we didn't belong there.

We asked if we could have a committee that could document the problem.

CEYER: What we wanted to do was, we wanted to see the data.

HOPKINS: It was very scary, I mean, for me, it was...

The future of my life in science was on the balance there.

And the dean came in, and he said, "You can have the committee, "but I don't think it can fix this problem, "because I don't know how to fix it.

"I think the problem is the nature of a very male-dominated culture."

♪ ADAM LEWIS: I went to Jane's house in Mandan, North Dakota.

It was her wedding.

And so she'd, I hadn't-- she'd been graduated for a couple of years or whatever.

And I was in the house, and her brother was standing there, and I was talking to her brother, and I introduced myself, I say, "I'm Adam..." And I said, "I went to Antarctica with them."

And he just stiffened.

He went... And just stiffened like a board, like... And instantly, I thought, "God, something is..." And he goes, "You were in Antarctica with her?"

And I was, like, "Yeah."

He said, "So you were there when all that took place."

And I was, like, "What, what took place?

Like, what do you mean?"

He said, "When Marchant treated her like (bleep) and tried to just ruin her, you were there."

So, for the next few minutes, I had this realization.

At Jane's wedding in Mandan, North Dakota, after talking to her brother, I was kind of standing there by myself with, like, a drink in my hand, going, like, "Holy (bleep), that must have been really bad for Jane."

My name is Adam Lewis.

And I met Jane when I became a graduate student.

So we went to Antarctica together.

And I was just in my office one day, just working, and an email pops up.

Jane says, "Hey, I've decided it's time to, to come out "and file this report about how Dave's treatment of women has been."

And you know, she's, like, "I know he's done it to other women, and I just think it, it needs to be dealt with."

She said, "You might need to write down what your experience is, what you remember."

So I don't have a choice.

My only choice is to just sit down and tell the truth.

That's my only choice.

I view Jane as a colleague and a friend.

And so why wouldn't I support her?

SANGEETA BHATIA: It feels like a really special moment in time.

♪ We're making inroads, but it's just too darn slow.

So, when I was a freshman in college, my best friend, who was also an engineer.

And we were sort of, like, together through the experience, which I think was really important for, for both of our retention in the profession.

We looked around, and we noticed that the classroom was about half women.

And, you know, I remember very clearly that we had a conversation about, "What is all the fuss about?"

Like, "There's plenty of women in this classroom.

Maybe it's just a matter of time."

And this is something I still hear, "Oh, it's just a matter of time."

And we looked around again senior year, and there was, out of 100 students, seven of us left.

And we sort of realized, like, "Oh, this is the leaky pipeline."

"This is disproportionate attrition."

♪ JOHNSON: In STEM, we have spent a lot of resources and time to get young girls focused on STEM.

So we know that we've been filling the pipeline.

The problem is that sexual harassment actually creates many leaks in that pipeline.

So we're doing a lot of work, but some of that work is actually being undone.

BHATIA: Why do you move away from a profession and choose a different one, you know?

That's sort of a collection of personal choices, but part of it is the culture.

There's a whole body of social science that has emerged where this is actually no longer a mystery.

♪ CORINNE MOSS-RACUSIN: I assumed that the study that we ultimately did or something similar would already have been done.

I was just interested to see, what is the experimental evidence of whether or not there's gender bias amongst the scientific community?

And I was surprised to see that that study had not yet been conducted.

So that's really what we immediately dug in to pursue.

The methodology of the study is really simple.

We describe a student who's applying to be a lab manager, in this case.

But the qualifications, the thing that participants read-- you know, their application-- is identical.

Except half of our participants are told that the student is a woman, Jennifer, and half are told that the student is a man, John.

So any differences at all in our conditions or how the participants react to these two students is attributable solely to the student's gender.

♪ We worked hard to recruit a representative sample of STEM faculty from around the country, and we sent half of them the application from Jennifer and half the application from John.

We told them that this was a student who had actually applied to be a lab manager somewhere in the country over the course of the last year, and that, for this new mentoring program, we needed their candid assessments of the student.

(mouse clicking) I remember the day I was sitting at my computer doing the first pass of data analysis for this, and I thought I had something miscoded, because I just didn't expect to see the same picture over and over again.

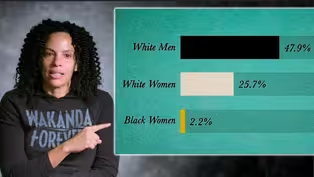

The female student is rated as inferior to the male student on every dimension that we assessed.

She's rated as less competent.

She's less likely to be hired for a lab manager job, less likely to be mentored by a faculty member, and given a lower starting salary than the identical male student.

The only difference between them is their gender.

And so we're really quantifying gender bias.

Not every woman contends with this identically.

Women of color are targeted in ways that are more complex, more insidious, and just more common.

(door opening) It's not always who you might think is going to be demonstrating these biases.

Bias comes from normal cognitive processing mechanisms.

And what that means is that really well-intentioned folks tend to display these sorts of very pervasive biases.

It's not sort of an evil cartoon of someone who's delighting in thwarting the progress of, of smart women-- it's all of us.

MAHZARIN BANAJI: Consciously, I could say I have zero bias.

To me, men and women who perform the same are equal.

But I think we're in those very early moments in the science where we're able to actually get snapshots of what's inside our mind of which we don't know.

BANAJI: So what we're going to do today is, you are participants in a couple of little exercises.

I hope you find this as intriguing as I did when I first took this test.

This test is called the I.A.T., or the Implicit Association Test.

BANAJI: The I.A.T.

has a very simple idea that underlies it.

The idea is that if two things have something in common, we'll be more easily able to put them together.

And sometimes this just happens in our experience.

Salt and pepper go together.

They're opposites in one sense, but they go together, because we combine them.

The word "king" and "queen" go together.

This is not a hard idea to imagine.

And so we use this idea to argue that if two things have come to be associated over and over again in our experience, whether we know it or not, we will be faster to put them together.

Nobody has any trouble understanding why this might be.

(laughs): It's a no-brainer, as a neuroscientist might say, okay.

So imagine that in the test, you're asked to do something very simple.

BANAJI: A word is going to pop up in the middle of the screen.

You're going to see names of men and women.

You're also gonna see words that are in two categories, family and career, and the career part that I've chosen, think scientific career.

Words for career are words like "scientist," "laboratory," "biologist."

Words for home are going to be words like "marriage," "kitchen," "children."

All you have to do is put the two together, right?

So, if the name is a male name or the word is a career word, you will say, "Left."

And if it's a female name or a home word, you will say, "Right."

Okay, you got it?

Keep that in your mind.

Oh, and you have to go super-fast to do this.

By super-fast, I mean, like, 700 milliseconds, meaning faster than a second to make each response.

Okay, so, simple, ready... Go.

STUDENTS: Left, left, right, right, left, left, left, right, right, right, right, right, left, left, right... (students stumbling and slowing) Left, left, left, right, right.

BANAJI: Excellent.

BANAJI: The trouble arises-- this is what makes it a test-- that we now flip these.

And now we'll do the other version.

If it's a female name or a career word, like "scientist" or that, you'll say, "Left."

If it's a male name or a house word, you will say, "Right," okay?

Everybody ready to go?

Go.

STUDENTS (hesitantly): Left, left, right, left... (students disagreeing and hesitating) (continue hesitantly) (slowly): Right, left, right... (disagreeing and chuckling) (responses stop, students exclaiming softly) BANAJI: Okay.

So, as a colleague of ours said, you don't need a computer to measure this bias.

A sundial will do.

(laughter) And that's because the effect is palpable.

Now, if you were one of the first people in the world to ever take this test and you made the test, your first reaction when you take this test should be, "Something's screwed up with the test."

At least that was my view.

BANAJI: I thought I could do this.

So I take the test, and it turns out I can't do it.

When I say, "I can't do it," I mean that I can, but with a lot more time and more errors in what I'm doing.

And the feeling you get as you take this test is one of utter despair.

(laughs) I ought to be able to associate female and male equally with science.

I am, after all, a woman in science.

This should not be so hard for me to do.

To discover that I cannot do that, I think, is profound.

♪ HOPKINS: Recently somebody had showed me an email they'd received from a very distinguished scientist who happens to be a colleague of mine-- so I was particularly upset by it-- saying that he had looked very carefully and had seen no bias or prejudice against women during his entire career, and therefore he was confident that such a thing did not exist.

And I guess, you know, at this point in time, 2019-- this email was a few months ago-- I just was shocked by this.

These are great scientists.

How can they not know this?

How can they not believe this?

If they know it, don't they believe it?

This worries me a lot.

So when I hear stories like the one you tell, that your male colleague believes that he's never seen it, I have two kinds of responses to it.

One, I understand that he may be truly unaware and genuinely believing that he's looking for it and just not seeing it.

It's in the nature of this beast that we're trying to identify.

It's invisible.

But then I also feel that he has no business saying what he did, because today, the evidence is so much more clear that he need not rely on his own personal experience.

He just needs to look at the data.

That's what he'd want us to do for his science.

He'd say, "Mahzarin, whatever you may think "about turbulence or whatever, that doesn't matter.

"That's your... intuitive experience "of the physical world.

But you need to know the research."

And I would say the same to him, because the time has passed now for saying, "I don't see it anywhere."

And that's why we should be concerned that anybody who says it's not happening, or not happening anymore, is just made to retract those words, 'cause they can say, "I, I'm not going to change my behavior, I don't care about it," all of that.

That's their...

But they cannot say that the evidence doesn't exist.

♪ BANAJI: My field, broadly speaking, is discovering that human beings may not be the people they think they are.

That they are far more fallible than they may have thought.

Who's competent?

Who has potential?

Who's brilliant?

We find very clear evidence that men are preferred to women for the same accomplishments.

♪ Implicit bias is something that we all carry in our heads.

How could we not?

We are creatures of our environment.

We are creatures who learn.

♪ When I see a certain set of patterns, that impinges on me in some way, and it leaves a trace.

Bill Nye the Science Guy.

Okay, now let's let that cook there for a while and make some more hydrogen... BANAJI: And that trace is now a part of me.

This is where the power of technology actually can be used to advantage to, in a sense, program our minds to be what we want them to have in them.

(bird squawking) BURKS: Before junior high, I would've been really hard-pressed to name a woman scientist.

I would have been extremely hard-pressed to name a woman scientist of color.

'Cause I didn't see any.

And science is a way to view the world.

It's also everywhere.

You can find it anywhere.

Yes, even in "Game of Thrones."

BURKS: Beyond the bench, I'm also a science communicator.

Video games can be complicated, but they're not rocket science.

BURKS: I'll be on podcasts, in different videos, and sometimes I get to be on television.

DIRECTOR: Roll cameras A, B, and C. Tape one, take one.

BURKS: Representation always matters.

You know, there's the whole saying of, "If you see it, you can be it," right?

It's getting better, but there used to be a time, right, when you would say, "Okay, what does a scientist look like?"

And it was, like, you know, white guy with crazy hair, you know, whatever.

And now it's, like, "No, it's a Black woman with crazy hair."

You can only report your sample, then, in a significant... BURKS: By its very nature, science itself should always be evolving.

Who is asking the questions, and how they're asking them, and who gets supported does determine the field.

The diversity of people in science can really set the outcomes.

So that's actually emboldened me to just be more authentically myself.

I did it!

BURKS: Yes!

It took me a while, 'cause Ralph kept distracting me, and then Joseph did, and so I'm going to blame them and not me.

Okay.

(laughing) So, yeah, this is what I have right now.

I have it all prepped and ready... BURKS: I might as well have more fun, wear silly clothing, and talk about zombie chemistry and wear my hair the way I want.

Not trying to chase this mythology of what a scientist is.

♪ (wind howling, birds twittering) ♪ (knocking on door) (door opens) WILLENBRING: Hello!

LEWIS: Jane!

Hey, Sylvie.

Hi!

Good to see you.

Oh, it's been a long time.

What a great house, oh, my gosh.

Oh, yeah, well, it's going to be great someday.

LEWIS: Do you remember walking back that time, when you and I and Brett were out there, walking back into the wind?

(chuckling): Yes.

My nose froze, right?

Yeah, and I got frostbite on my tuchus.

Yeah.

Going to the bathroom.

That's the worst.

Oh, God.

I'd still be going there.

I would still be a college professor, and I'd still be going there if I didn't have to go to the bathroom.

In Antarctica.

(laughing) Yeah.

You know, when I was writing my Title IX complaint, it was incredibly cathartic.

Mm.

I just, like, wrote it, and then just started bawling.

When you're writing them all out, one after another... Yeah.

You know.

It's, like, yeah, that happened, and then that happened, and then that happened.

And you start thinking, like, "How did this even..." And it's, like, "Well, they were different days, and, you know, I had thought it would get better."

Yeah.

And you know, you have, like, this whole mindset of, like, hoping for the best, even though you really think that it's probably not going to go well.

Mm-hmm.

I never knew how much it bothered you.

I didn't know.

You didn't show it to me, so I didn't know.

I mean, I knew he was being a complete dick to you, but I didn't know that it was getting to you.

Yeah.

It was hard to navigate.

Like, I knew, I mean, it's... Obviously, it was an issue.

But it just was, like, "Okay, well, Jane's kind of dealing with it," and whatever.

I do sort of have a tough cookie sort of bravado about me.

I mean, I should have seen it more.

I feel a major regret, 'cause I didn't help.

When I wrote that out, I was, like, "God, the pattern is so clear!"

Some of the things that you tell me and that I've heard from other women, I just-- it's unfathomable.

I didn't know.

And most of the men that I know, all these guys that I went to Antarctica with and all my professor friends, whatever... Mm-hmm.

We-- they would not do that, right?

Mm-hmm, mm-hmm.

So, when you hear these stories, you're just, like, "What?"

Right.

I'll tell you a story.

I think I've told you this before.

So, I was in Europe and I was at this glacial conference thing, this EU-run thing.

Yeah.

With a whole bunch of students, and there was this old glaciologist there.

He's, like, about 60 years old.

Anyway, we were all out at the-- in Italy, and we're all out at the bar.

He takes his hotel room key, and he starts just going down the line.

And you couldn't really hear what he was saying, but he would go up to a female student and be, like... (imitating indistinct conversation) And then he would put the key on the table, and they would all be, like, "Yeah, yeah."

And they'd just flick the key right back to him.

Mm-hmm.

A couple of minutes later, he would sit down at the next table with a, with a girl, and he'd be, like, "Yeah, so how are you doing?"

Key goes out on the table, and every time, the girl just was, like... (scoffing): "Yeah."

(chuckling): Slaps it right back at him.

But it didn't deter him at all, and he just went to the next one, right?

Mm-hmm.

And he's obviously, like, lecherous and all that kind of stuff.

But I always, I was always impressed with those women, that they didn't seem to take any...

They didn't take it in on themselves.

They were just, like, "Yeah, no, no, thanks."

Right, but it's also, like, bad to, like, sort of be proud of them for, like, just laughing it off and not making a big scene about it, because, really, someone should do that.

Do you think they should have?

But what we have is a selection bias of, all of the people who make a big scene like that are kicked out of science.

And so it's only the people who, like... (fake laughing) ...and push the card away that actually are able to, like, be the women who stay.

I see, yeah.

Imagine getting hit on at a conference, and then, like, someone else says, "Hey, do you want to talk about your poster over a beer across the street?"

You think nothing of it, right?

You're, like, "I'll try to ignore that being hit on "earlier in the day.

"I'll go across the street, have a beer with this, you know, big-name guy."

And then you go across the street, and you have a beer with this guy, and then he hits on you, too.

And then you walk back to your room with someone who, you know, was your lab mate, and they say, "What did you think he wanted?

"Do you think he was interested in talking about science with you?"

(laughs) How does that make you feel?

You know?

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

And then you actually have someone who, you know, like, is, behaves completely professionally, values your opinion.

And then you have some success in life, and then that same lab mate is, like, "Oh, I know why she got that.

"She had a beer with the guy, and then she probably slept with him later on that night."

And then, even though nothing happened, you've been hit on twice, you didn't do anything wrong, and now you have this reputation for having some success because you were seen having a beer with someone.

That's the kind of crap that, like, that second group of people does.

♪ It's sort of, like, what is it?

A ton of feathers is still a ton.

♪ (projector clicking) ♪ LEWIS: Looking back on it, these really, really capable women are walking into a headwind that I didn't have.

And sometimes they come up against a real brick wall in a guy like David Marchant.

♪ You know, I saw that Dave was taking some special joy in tormenting her, calling her "Crazy Jane" all the time.

"Hey, Crazy Jane, Crazy Jane."

And I think one of the reasons that he got really into it is that she really was good at not showing that it was bothering her.

So then he, he turned the dial up.

Didn't seem like it bothered her.

He turned the dial up.

Didn't seem like it bothered her.

And so, I'll be honest, I honestly did not...

I mean, I knew he was being a dick.

I knew it, but it just didn't seem to bother her.

She seemed to just laugh it off.

With the Dave and Jane thing, it comes back to me.

Many, many other times in my life, I have jumped to the defense of the weaker person.

But with Jane, I didn't see it, and it's just pure stupidity.

It was pure...

I just didn't open my eyes to what was going on.

♪ ♪ AZEEN GHORAYSHI: I have reported on sexual harassment in the sciences since 2015.

The frustration with inaction is, is why we saw this wave of women coming forward to publicize their stories.

I don't think that most people's first option is to, you know, go to a reporter and talk about the problems they dealt with as a graduate student, you know?

I think that very much happened as a result of a lot of other failures in the, along the way.

Many of the women that I've spoken to in the stories that we've reported here about sexual harassment have left the field.

And they have said very clearly that this is why they've left the field.

That it was either the experience itself, or it was the process of trying to do anything about it that eventually made them throw their hands up and be, like, "Screw it.

"This is not...

I don't have to deal with this."

♪ (engines roaring) REPORTER: Liftoff of America's first space shuttle.

And the shuttle has cleared the tower.

WOMAN: I was seven when the space shuttle first went up.

I decided right then and there that I wanted to be an astronaut.

I don't think I realized how obsessive I was about it.

It turns out most people didn't spend their nights listening to the same recordings of all the Apollo missions, you know, time after time.

ASTRONAUT: 2,500 feet.

MAN: Clear.

WOMAN: I just also loved science in college.

I wanted to take all the sciences, which I did, like, took a class in every science along the way.

I enjoyed a lot of the other sciences, but geology was my passion.

(cheers and applause) One of the unspoken rules was that you needed to have either a PhD or be coming out of the military as a pilot.

And so that's what put me on the track of, "Must get my PhD."

PILOT: Two, one, nose gear is ten feet.

WOMAN: When I got the call back from B.U., they said they would love to have me.

I was admitted, and I could work in the program that I had applied to, but they also had this new professor who had just come in and was going to be doing Antarctic work.

So I was the first grad student of Dave Marchant.

(traffic noise) So I arrived in September.

In my second week, Dave told me that he did not want a woman as a graduate student.

I said, "I don't have a gender-neutral name, so it was clear that I was a woman when I was applying."

I can't remember exactly what he said, but it was more or less that the department had foisted me upon him.

My experience when I was in Boston was fairly atrocious, but I really wasn't mentally prepared for what would happen when I got down into Antarctica.

♪ It was bullying from day one.

He was using epithets all the time, "whore," "bitch."

And then I remember the first time he called me (bleep).

Later on, he would tell me that he did not believe that women should be on the ice in Antarctica, and we're altering the science on the ice for worse.

♪ In order to do scientific work down in Antarctica, you need to apply for funding through the National Science Foundation Polar Programs.

So there aren't alternate sources for funding if you want to do work there.

And part of how Dave derived his authority was because he helped to decide who got the funding.

♪ It was the middle of the summer in Antarctica, and we walked outside of the camp because he indicated that he had something that he wanted to tell me.

He told me that he had decided that I would have no future in, in any polar studies, and that they would make sure that I got no funding.

My whole world was disintegrating, and then he, like, grinned at me, and walked off.

And when we got back, I went to the chair of the department at the time, and explained all the circumstances.

And it was a woman.

She was sitting behind a desk in a fairly darkened room, and it was a big wooden desk.

She said, "You can go through this, but Dr. Marchant "has a sterling reputation, "brings a lot of money into this department, "and wouldn't it just be easier if you just finished a master's degree and left?"

And I was floored.

The department judged that running one woman out of science was much less of a hassle than running a man out.

Leaving without a PhD meant not applying to be an astronaut.

And it was the end of the dream that I had had.

Who knows if I'd ever actually have become an astronaut?

But, if it was going to end, I would have wanted it to end on my terms.

HOPKINS: For me, it was a conflict that was never to be resolved, even though I loved the science that was happening.

So I just couldn't do it any longer.

I was about 50, and I thought, "There are two choices here, either..." I could retire, but I'm not rich enough to retire, and never work again.

There's no other thing I'd rather do outside of science.

I just loved it.

Somehow, I-- this is worth fighting for.

I'm going to fight enough that I can go in the lab and do an experiment, and somebody's not going to come and make it impossible for me to do it, or ruin it after I have done it, or take all the credit for it once it's done, or make sure that something bad...

I'm going to fight for that because I just have to do this.

I want to be a scientist.

If you believe that passion for science, ability in science is evenly distributed among the sexes, if you don't have women, you've lost half the best people.

♪ Can we really afford to lose those top scientists?

♪ BANAJI: Often, people talk about the cost to women.

For now, I want to put that aside and just talk about the cost to the world of science.

I mean, how much are we costing ourselves?

How many great discoveries have just been lost to us because we didn't have the eyes to see?

REPORTER: A study of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology was launched by female faculty members fed up with unequal treatment.

REPORTER: At M.I.T., female professors have been learning lessons the hard way.

When the women compared notes, they found they all had similar problems.

That triggered a five-year study.

What they found were salary inequities, lack of advancement... McNUTT: As the evidence started coming in, it was really clear that there were major discrepancies.

CEYER: On the average, the laboratory space for women was significantly less than the laboratory space for men, and it was clear that the women were paid a lower salary than the men.

ROYDEN: M.I.T.

was losing female faculty hires because of the childcare issue.

There was no childcare anywhere in the central campus.

I think it took all of that to make it comprehensible story.

♪ It came to be known as the M.I.T.

Report.

It was just a summary of what we'd done with some data in it.

♪ I said, "We've got to ask Chuck Vest if he'd like to "put a comment to go with the report.

We don't want anyone to think that we blindsided them."

♪ ROBERT BROWN: It was a long time between the full report and then the decision.

I would think it's almost months.

Definitely weeks.

It was very complicated for the university.

You have to, I think, put this whole thing in the context of a university that really prided itself on being a meritocracy.

♪ HOPKINS: You thought no president of any university would ever understand, much less acknowledge publicly.

He struggled with exactly the criticism that I think everyone knew we would get.

♪ HOPKINS: But then something really amazing happened.

He endorsed the report.

He wrote this comment, which really is, I think, the reason the M.I.T.

Report became so well-known.

"I have always believed "that contemporary gender discrimination "within universities is part reality and part perception, "but I now understand that reality is by far the greater part of the balance."

CEYER: He came out and said, "There has been discrimination, "and there has been bias, and we're going to go forward and rectify this."

What the report made us do is own the problem.

CEYER: Because it was based on data, you can't refute it.

♪ BROWN: It was a ripple that, you could feel that resonance, and that's because it was real.

CEYER: We all were amazed at the response.

HOPKINS: After the M.I.T.

Report, I was invited to give so many talks, and I went around the country, and I met so many women who had put so much time into this problem.

McNUTT: Women everywhere could go to their department heads, to their provosts, and say, "Why are we not doing this?"

And they did.

BHATIA: The last 20 years for me have been sort of a slow continuous change.

I was a graduate student at M.I.T.

in the '90s.

I was one of very few women.

And then when I came back to be on the faculty of 2005, every step of the way, someone has been quietly watching my salary, making sure that it was equal.

So I have benefited from the work that they did.

And I try to do, you know, that for the next generation.

BROWN: It was a turning point for me as a university administrator.

I remember going to a meeting of provosts not long after that and getting browbeat by a number of provosts-- I'm not going to say who-- who said, "It's not in my institution."

There still is bias.

People still have implicit bias and explicit bias.

You know, these are tough societal problems, and you can't lose the energy, because you won't solve the problem unless you build in, you know, systematic structural change that can keep working over a long timeframe.

WOMAN: Nancy, hi!

How are you, Nancy?

So good to see you.

How are you?

I can't remember the last time I saw you.

How are you, how are you?

Good to see you.

You're wearing a different costume!

Oh, so good to see you.

Nancy, this is such a crazy thing.

HOPKINS: It took that group working together to take this problem on.

It really couldn't have been done otherwise.

MALANOTTE-RIZZOLI: Sylvia, myself, Penny, Nancy, Vicki.

We were much younger.

(laughter) CHISHOLM: Everyone was.

20 years.

You know, this kind of thing takes somebody who's passionate, who's willing to give their life to it, and who has tremendous courage.

The first toast is to Nancy, and the second toast is to all of us.

(laughter, chatter) If you go back and read the things that we wrote, they're brilliant!

(laughter) ♪ BURKS: So we are in Quebec City for the Canadian Chemical Society meeting.

I am speaking at the meeting.

I always get really, really nervous.

A skosh of it might be impostor syndrome, which a lot of people get.

But I also think part of it is the expectations sometimes for speakers from historically marginalized groups are higher.

(indistinct chatter) WOMAN: "The Washington Post," "Chemistry World," and "Scientific American" have all featured her pop-culture chemistry writing.

And if you haven't yet checked out her blogs and podcasts, they make really excellent content for lectures.

Please join me in welcoming Dr. Raychelle Burks to the stage.

(applause) BURKS: So I want to kick off my talk by first talking about code-switching.

So how many folks are familiar with code-switching?

And so it's a linguistic term.

Oftentimes in linguistics, it's considered between languages.

Definitely when you're learning a new language, right?

But in the last ten to 15 years, this has really been expanded, and this is actually a great visual of what code-switching is.

So look at how he's doing this handshake... And then with Durant, right?

There's a familiarity there.

You code-switch, right?

If you're at work, talking to your colleagues, talking to the dean, or at home, you switch your styles.

You may also switch your language.

Even though we all do it, the historically marginalized do it sometimes for a different reason, right?

We do it because we're told in implicit and explicit ways that basically everything you are, from the top of your head to the bottom of your toes, needs to change.

Your hair, your "ethnic dress," your mannerisms, they got to go, right?

And we often do it by calling it "professional" or "professional standards," right?

And what we need to realize is that our so-called professional standards or professionalism, who got to decide that?

Who got to make those rules, right?

'Cause I don't recall making a rule that my hair needed to be straight.

And I have absolutely been told, you know, "Before you go to that talk, are you going to make your hair look more professional?"

K through 12, college, graduate school, and now we hear this kind of thing.

"Science is apolitical," right?

"It's objective."

"It's free from bias where only the best rise to the top."

And I did believe that, okay?

And maybe there are some of you sitting in the audience that are, like, "No, that's absolutely true.

And I refuse to hear differently."

And it's not true, because science is a human endeavor, and that means that it contains and is subject to all of our brilliance and all of our bias.

And we tend to focus on the brilliance part, but remember, there's an "and bias."

This is advice that I've gotten, and I'm passing it on.

Take care of yourself.

Take care of you, take care of others.

You cannot do everything on your own.

You need enough of your allies, well positioned, to make something happen.

It's about doing.

The correction requires action.

We can do better, we can get better, and we will be better together.

Thank you.

(applause) ♪ Awesome.

There you go.

Perfect.

WILLENBRING: So we're going to take a sample, take it back to the lab, and crush it, and then we do all kinds of things to it.

(chuckles) You'll take that tiny little powder that you end up with, and you'll pack that into a little target that you send to the accelerator mass spectrometer, and the whole sample that you end up with is, like, the head of a pin.

Sometimes we use kilograms of samples, and we'll end up with just this little tiny thing that will disappear if you sneeze, so we don't do that.

(laughter) WILLENBRING: One of my goals in mentoring is to be someone that I needed when I was younger.

All right, so do we measure or should we keep going?

WILLENBRING: Maybe a little bit more.

(hammering) WOMAN: Jane's a great adviser.

She really is somebody who I can admire and look up to and take as a role model in many different ways.

WILLENBRING: Oh, that's the money right there.

Ah, perfect.

WILLENBRING: If you hit it a couple of more times.

♪ I think about what would have led the faculty committee to have come to that decision to let him back on.

They said that he would be able to resume his normal activities after a certain period of time.

So I was in sort of disbelief.

But the president, fortunately, thought something different.

BROWN: I'm Bob Brown.

I'm president of Boston University, and before that, was provost at M.I.T.

♪ NEWS REPORTER: Boston University has fired a professor accused of sexual harassment.

In a letter to the faculty Friday, B.U.

president Robert Brown announced that after a 13-month investigation, the board of trustees voted to terminate Dr. David Marchant's employment.

WILLENBRING: When I heard the news, I was a little bit conflicted, because on the one hand, it was great that he was fired and wouldn't be able to do anything to other female trainees.

But on the other hand, in so many cases, there's not that justice that happens.

(Sylvie speaks indistinctly) (Willenbring laughs) A lot of people, especially male scientists, you know, when they heard about my story, I received a diversity of responses.

Some people avoided eye contact.

Some people wanted to have nothing to do with me.

Some people wanted to talk about it and ask what they could do, which I think is a great response.

One thing that's been really impressive has been how much people have wanted to make change as a result.

The Science and Technology Committee opened an inquiry.

They were shocked that someone who'd been harassing women for decades had received millions of dollars in National Science Foundation funding.

BARBARA COMSTOCK: The Committee on Science, Space, and Technology will come to order.

(gavel raps) And I now recognize Dr. Clancy for five minutes to present her testimony.

We scientists do this work because we want to give the best of ourselves to the advancement of science.

Women keep trying to give us their best, and we blow ash in their faces and push them down mountains.

The way we've tried to fix this problem isn't working.

We have decades of evidence to prove it.

Let's move away from a culture of compliance and towards a culture of change.

♪ ♪ HOPKINS: Despite all the progress, and it's tremendous progress, women still grapple with these problems.

People had never really looked at the data in the way that we looked at it as a committee.

So I kept memos, just copies of memos.

And what's astonishing to me when I look at all of this is the amount of time and the amount of work that went into doing this, asking people to come to meetings and the amount of effort it took to try to see... And I think about, you know... it makes me realize, you know, that at the time, I was spending 20 hours a week or something on this and then doing my job the rest of the time.

It makes me sad.

It really does.

You know, you sort of wonder in your life, would you have done it differently?

And, gosh, I don't know.

I couldn't have lived without science, but I wouldn't live through this again, I'll tell you.

So I don't know what the answer should have been, would have been.

I still don't know.

It can still...

Even now, just, just thinking about it, you know, that it was this way.

Such a waste of time and energy, when all you wanted to do was be a scientist.

What on Earth?

♪ Look at the talent of these women.

This is what you lose when you do not solve this problem.

♪ And that's really what it's about.

It's about the science.

♪ ♪ REPORTER: As misinformation and so-called fake news continues to be rapidly distributed on the internet, our reality has become increasingly shaped by false information.

Many people don't know the difference between something real and something created to deceive them.

SAFIYA NOBLE: I spent about 15 years in advertising and marketing, and while I was there, Google arrived on the scene.

I understood the transformative effect that this search engine was having in helping us curate through all kinds of information.

But I was surprised, having just left advertising, that everybody was thinking about Google as this new public trusted resource, because I thought of it as an advertising platform.

Most people who use search engines believe that search engine results are fair and unbiased.

The public, and especially kids and young people, use search engines to tell them the facts about the world.

♪ One weekend, my nieces were coming over to hang out, and I was thinking, "Oh, let me pull my laptop out "and see if I can find some cool things for us to do this weekend."

I just thought to type in "Black girls," and the whole first page of search results was almost exclusively pornography or hyper-sexualized content.

In 2012, I started to see some of the results changing.

Google had started to suppress the pornography around Black girls.

Unfortunately, still today, we see pornography and a kind of hyper-sexualized content as the primary way in which Latina and Asian girls are represented.

"What makes Asian girls so attractive," "Asian fetish," "hot ladies from Asians," "see who we rank number one in 2020," "tender Asian girls," "meet world beauties."

♪ This is the study that was done by the Markup that replicated my study from ten years ago.

They found that Black girls, Latina girls, and Asian girls, those phrases were-- look-- so profoundly linked with kind of adult content.

Zero for white girls, zero for white boys.

There are so many racial stereotypes and gender stereotypes that show up in search results.

What about actual girls and children who go and look for themselves in these spaces?

It's very disheartening.

When women become sex objects in a space like this, it's really profound, because the public generally relates to search engines as kind of fact checkers.

♪ Before we were so heavily reliant upon a database, we used something like a card catalogue.

♪ We didn't rank content, it was alphabetical.

It also might be by subject.

It's a summary of the organization system we call the Dewey Decimal System.

NOBLE: Now when we're in a subject, we know there is a lot in relationship to that one item that we might be looking for.

We might go look for a book in the stacks, for example, and find that there's hundreds of books around that one that tell us something about that book, and we might serendipitously find all kinds of other bits of information that are amazing.

But we can see a little a bit more about the logics of that.

We don't understand the logics of how certain things make it to the first page in a search.

Google has a very complicated and nuanced algorithm for search.

Over 200 different factors go into how they decide what we see.

Of course, they're indexing about half of all of the information that is on the web, and even that is trillions of pages.

AD ANNOUNCER: Billions of times a day, Google software locates all the potentially relevant results on the web, removes all the spam, and ranks them based on hundreds of factors, like keywords, links, location, and freshness-- all in, oh, 0.81 seconds.

NOBLE: The whole premise of a search engine is to categorize and classify information.

A lot of the content that comes back to us on the internet, it's in a cultural context of ranking.

We know very early what it means to be number one, so ranking logic signals to us that the classification is accurate, from one being the best to whatever is on page 48 of search, which nobody ever looks at.

(keyboard clacking) Part of what it's doing is picking up signals from things that we've clicked on in the past, that a lot of other people have clicked on, things that are popular.

So an algorithm is, in essence, a decision tree.

If these conditions are present, then this decision should be made.

And the decision tree gets automated so that it becomes like a sorting mechanism.

Google's very reliable for certain types of information.

If you're using it in this kind of phone book fashion, it's fairly reliable.

But when you start asking a search engine more complex questions, or you start looking for knowledge, the evidence isn't there that it's capable of doing that.

It's this combination of hyperlinking, it's a combination of advertising and capital, and also what people click on that really drives what we find on the web.

This is where we start falling into trickier situations, because those who have the most money are really able to optimize their content better than anyone else.

♪ There have been great studies about the disparate impact of what a profile online says about who you are.

♪ LATANYA SWEENEY: I was the first African American women to get a PhD in computer science at M.I.T.

So, I visit Harvard.